However, its recent rediscovery has gladdened the hearts of those of us who mourn species that have disappeared, and brought with it hope to the entire conservation community that all is, sometimes, not lost.

So, what exactly are they? Chevrotains are also known as mouse-deer, even though they are neither mice nor deer. They are ungulates (hoofed mammals), in fact they are the smallest ungulates in the world – just the size of small cat or large rabbit, weighing in at less than 5kg. They lack the antlers or horns that are typical of other ungulates, and instead sport tiny fangs. These tusk-like incisors are longer on males than females, so are thought to be used for competing over mates or territory. They are shy, solitary animals that walk curiously on the tips of their hooves.

Andrew Tilker is a biologist from Global Wildlife Conservation, the organisation that, alongside their partners from the Southern Institute of Ecology and Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research, announced the rediscovery. He says: “It’s a really cool species, and we’d long hoped to find proof they were still around.”

The silver-backed chevrotain was rediscovered as part of Global Wildlife Conservation’s Search for Lost Species programme. This is an initiative that seeks to find 1,200 species of animals and plants that are thought to be missing, and then put conservation measures in place to protect them. The silver-backed chevrotain was the first mammal to be found (hopefully the first of many) and conveys a valuable lesson: “We shouldn’t give up on them just because we haven’t seen them in a long time,” states Tilker.

There are 9 species of chevrotain in total – one species lives in Central and West Africa, the rest in South and Southeast Asia. The silver-backed chevrotain was known to have existed in Vietnam, sharing habitat with the more widespread lesser chevrotain. However, its name gives away the means of telling them apart, as the silver-backed chevrotain has distinctive silver or grey fur on its posterior which the lesser chevrotain lacks. What was known about the former species (and that wasn’t much) was from four specimens collected in 1910 that were used to describe the species. The last scientific recording was in 1990, when a hunter donated a specimen to scientists on a joint Vietnamese-Russian expedition to central Vietnam. What all these specimens had in common was that they were all dead – no one knew if any living silver-backed chevrotain still existed.

The odds were stacked against this being a possibility. Following the identification of the 1990 specimen, scientists called for a follow-up survey because the area in which it came from had undergone severe deforestation, and hunting was rife. However, no further search efforts took place and there were no more sightings. Given the fact that hunting pressure has increased considerably throughout Vietnam since 1990, the chances of finding them seemed slim.

As did the chance of enlisting local people to help with the search. The scientists first stage was to carry out interview surveys with local hunters and forest experts to obtain information on potential occurrences of silver-backed chevrotains. As hunting (using cheap but deadly homemade wire snares) is illegal, the scientists had to spend time with them to gain their trust before they were willing to talk. Yet in the end, the people they spoke to expressed concern about dwindling animal populations, as An Nguyen, the Global Wildlife Conservation scientist who led the expedition, explains: “People have become very concerned about how much wildlife has vanished in the past 5 to 10 years. They know it’s because of overhunting and the use of snares.”

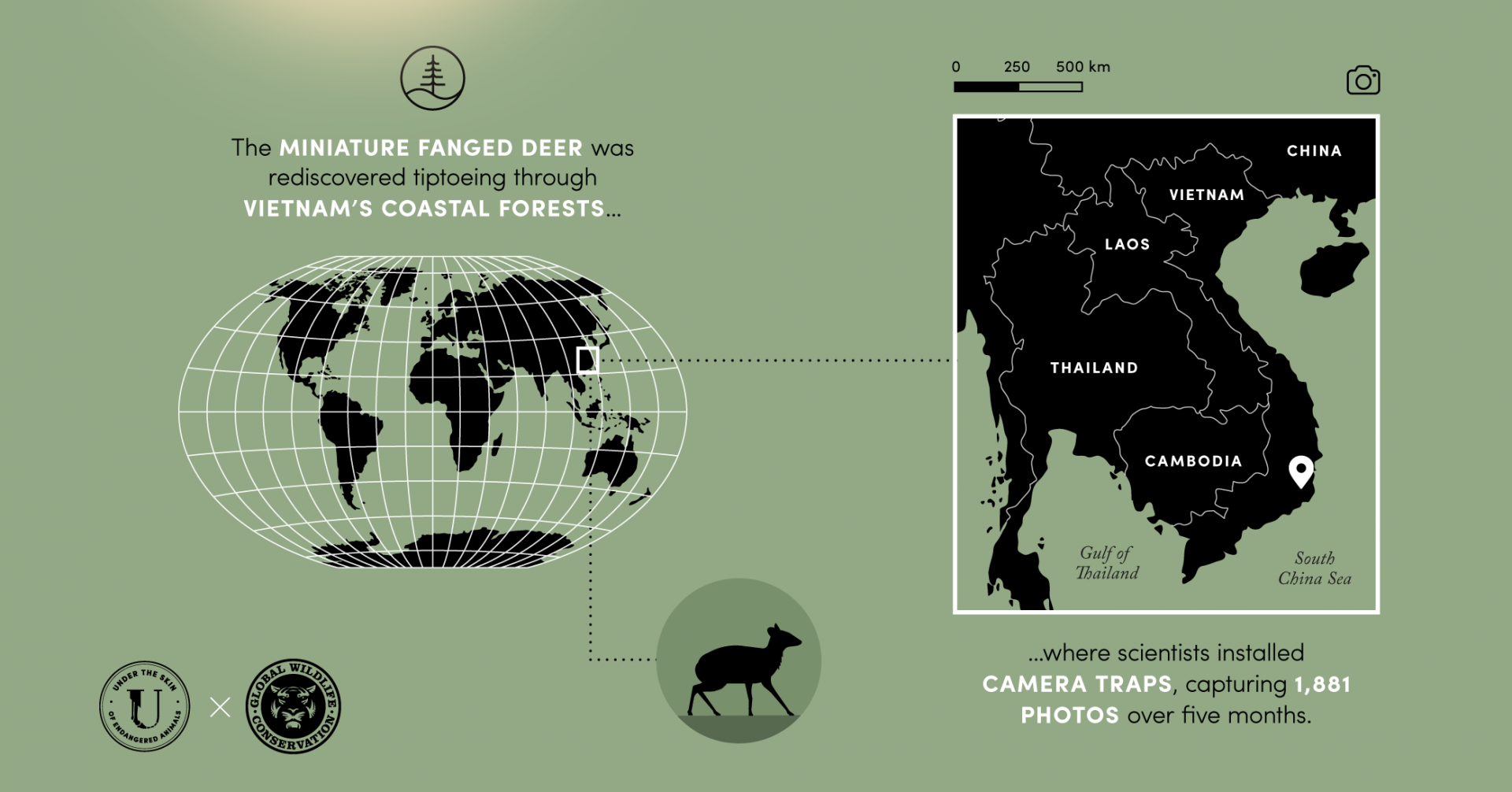

Out of 35 people interviewed, six reported the existence of two types of chevrotain that could be distinguished by the colour of their coat. Three people reported the presence of a single chevrotain with grey flanks. They also took the scientists to places in the forest where they had recently seen grey coloured chevrotains. Targeted camera traps, set up less than a foot off the ground due to the diminutive size of the species they were searching for, were placed in dry lowland forest. Between November 2017 and April 2018, the cameras took a total of 275 photographs of chevrotain that were identified specifically as silver-backed chevrotain. More intensive trapping in the same area between April and July 2018 revealed even more – 1,881 photographs. At last, they had the first images of the species in the wild and confirmation of its existence. An Nguyen describes his reaction: “The results were amazing. I was overjoyed when we checked the camera traps and saw photographs of a chevrotain with silver flanks.” He also added tick number 50 to his tattoo of sightings of mammals he has never seen before.

The rediscovery of this long lost species is great news for conservationists – a ray of optimism penetrating the normally dark skies of species extinction. But. Poaching, driven by demand for bushmeat in East Asia, is prevalent all over Vietnam. Wire snare traps are indiscriminate, catching and killing pretty much everything that walks on the forest floor, common or endangered, big or small, so bad that it results in “empty forest syndrome.” Wire snare poaching has already pushed other endemic deer-like species to the brink of extinction, such as the large-antlered muntjac and the saola, the so-called “Asian unicorn”, which was discovered in 1992 but has not been seen in the wild by any scientist.

The threat of poaching is so serious that the scientists had to weigh up the risk of increased hunting by drawing attention to the species versus gaining support and increased protection for it. Other conservationists questioned the announcement of the rediscovery, but it is a dilemma that those working with highly endangered species are forced to face – risk putting the animals in danger by revealing their existence or keep it quiet and watch them potentially fade away in silence. Ultimately, it is hard to save a species if no one knows it exists, and the scientists from Global Wildlife Conservation took measures to hide the chevrotains’ exact location, for example, by not providing GPS coordinates for their camera traps and not revealing the name of the forest they were found in.

The scientists are also confident that Vietnam is taking the situation seriously and, with adequate support and finances, can tackle the tricky problem of snaring. Increased enforcement has already begun at the site where the silver-backed chevrotains were discovered. As has further camera trapping, the beginnings of the first-ever comprehensive survey of the species in order to assess its population size and distribution, as well as identify threats to its survival. It is vital that more knowledge is gained – knowledge that will be used by Global Wildlife Conservation to develop and implement a conservation plan. Andrew Tilker says: “For so long, this species has seemingly only existed as part of our imagination. Discovering that it is, indeed, still out there is the first step in ensuring we don’t lose it again, and we’re moving quickly now to figure out how best to protect it.” The sighting must be followed by “on-the-ground” action.

For now, the silver-backed chevrotain is listed as ‘data deficient’ because no one can say how many individuals are left or where exactly they live. If one or two sites can be found with large and stable enough populations, then further protection measures can be put in place, such as education of local people and anti-poaching patrols.

Its long-term survival is most definitely not a given. But what this rediscovery does show is that we should never give up on other lost species. The silver-backed chevrotain went from being lost for at least 30 years, to found again in just a few months. The surveys conducted, although targeted, were not long in duration or expensive. Valuable information was also obtained by simply talking to local people. Perhaps such minimal efforts would yield just as good results for other species that have gone unrecorded for many years.

The hard work of conserving the elusive silver-backed chevrotain is underway. I had never heard of this species before their rediscovery was announced and I will probably never be lucky enough to see one. But I am sure I am not alone in being glad to know that they still tiptoe through the forests of Vietnam and hope that those toes manage to avoid the trap of a wire snare for many years to come.

Read more articles from our contributing authors and follow the project progress by signing up to the Under the Skin newsletter.